To complete your annual review for the year year, you must report on your teaching via Digital Measures.

ITAC offers Faculty Qualifications office hours via SignUp. These are two-hour drop-in sessions during which you can ask questions about the system ahead of our faculty review season.

TEACHING

All faculty are reviewed for teaching. Depending on their rank and workload assignment, faculty are also reviewed for scholarly/creative activity and service. Using the criteria given below, reviewers determine whether a faculty member “meets expectations,” “exceeds expectations,” or “does not meet expectations” in each category of review. If a faculty member is not expected to perform in a particular category, reviewers assign “NA” (“not applicable”).

Good university teachers have the following characteristics: competent and growing in their discipline; articulate; accessible to students; disciplined in their work habits; skillful in motivating students; effective in organizing courses; and careful in maintaining high academic standards.

In general, faculty who exceed expectations in teaching provide the review committee with detailed, thoughtful comments in their annual review report. Faculty also indicate what they have learned from evaluations and explain what changes, if any, they have decided to make in light of students’ responses. Faculty may choose to discuss information such as the development of new courses or modification of the content, format, organization, or use of technology in existing courses; development of teaching knowledge and skills through independent study, attendance at workshops, or other professional development activities; mentoring that extends beyond the classroom, such as training IAs, helping students revise work for presentation/publication, or advising students about graduate study or career options.

TEACHING NARRATIVES

1) You will write one 450- to 500-word narrative in which you reflect on your teaching, incorporating your end-of-course evaluations.

Tips for writing teaching narratives:

- Review the English Department Annual Review Policy on Teaching (pasted in above). This policy dictates the review committee's criteria when assessing annual review teaching narratives: “good university teachers” are “competent and growing in their discipline," “articulate," “effective in organizing courses,” and “careful in maintaining high academic standards.”

- Review last year's annual review, including the annual review committee's and the chair's feedback, before writing this year's narrative.

- Refer to the sample teaching narratives at the bottom of this page.

- Do not write more than 500 words.

Note: Using the "Courses Prepared and Curriculum Development" area in Faculty Qualifications should not be misunderstood as a substitute/alternative for teaching narrative that you paste into Comments on Teaching (Narrative) under Annual Review/Annual Review Narratives.

I. To report your teaching narrative . . .

Step #1: Log in to Digital Measures

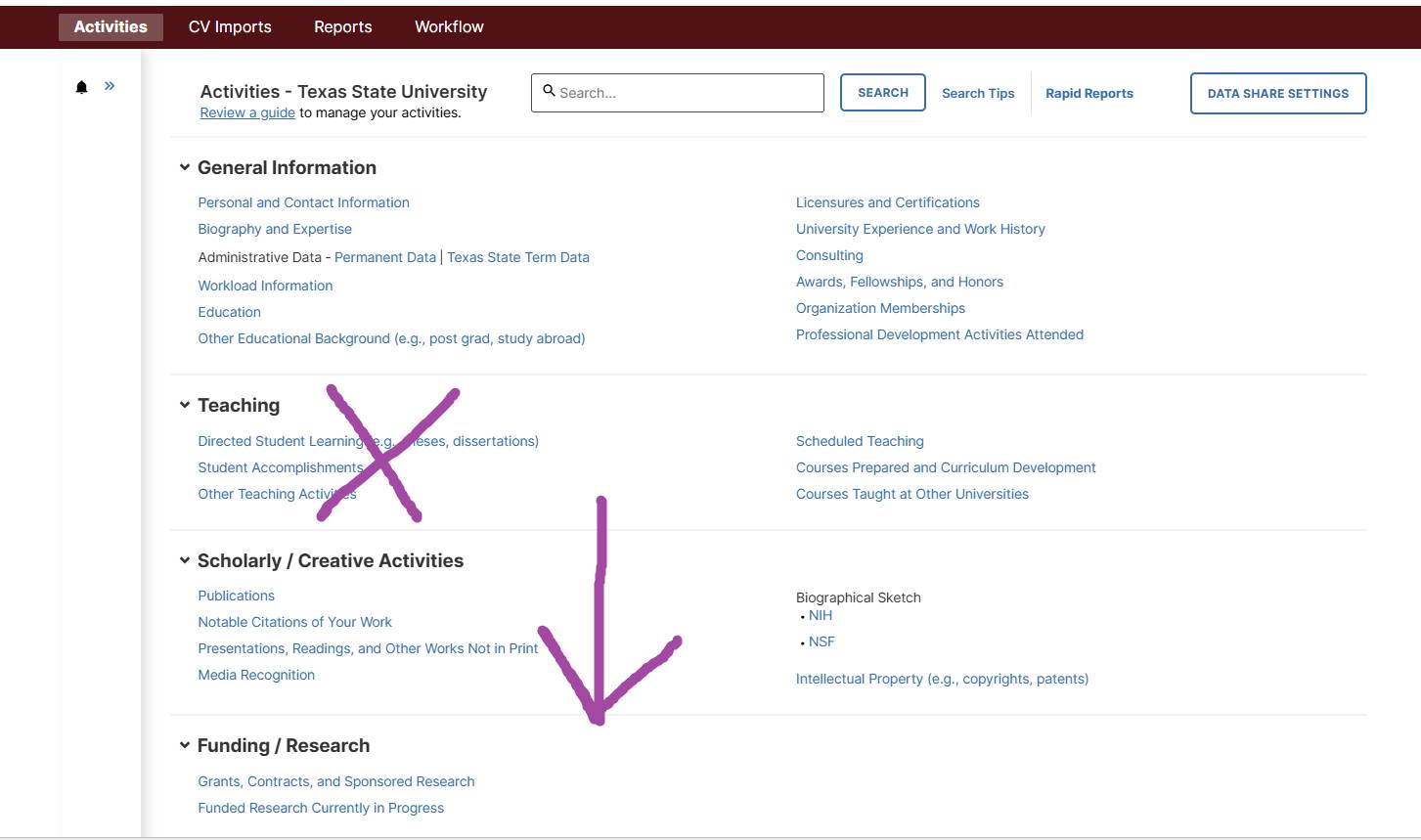

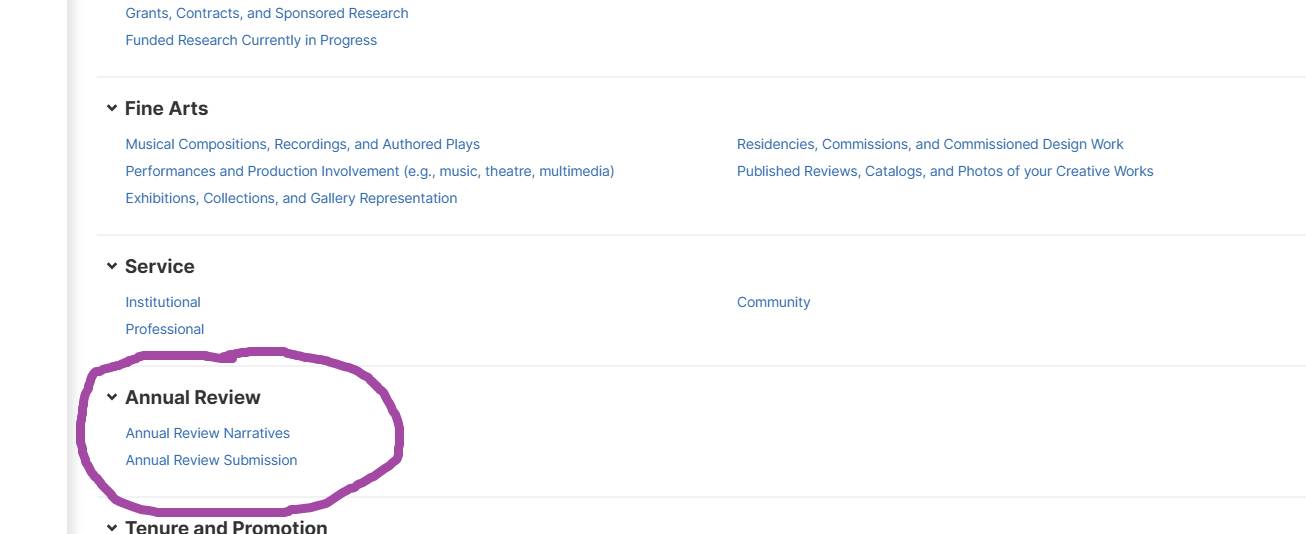

Step #2: SCROLL PAST Teaching to the bottom of the page and click to Annual Review and below that Annual Review Narratives. (Do not use the Teaching section for your annual review narratives.)

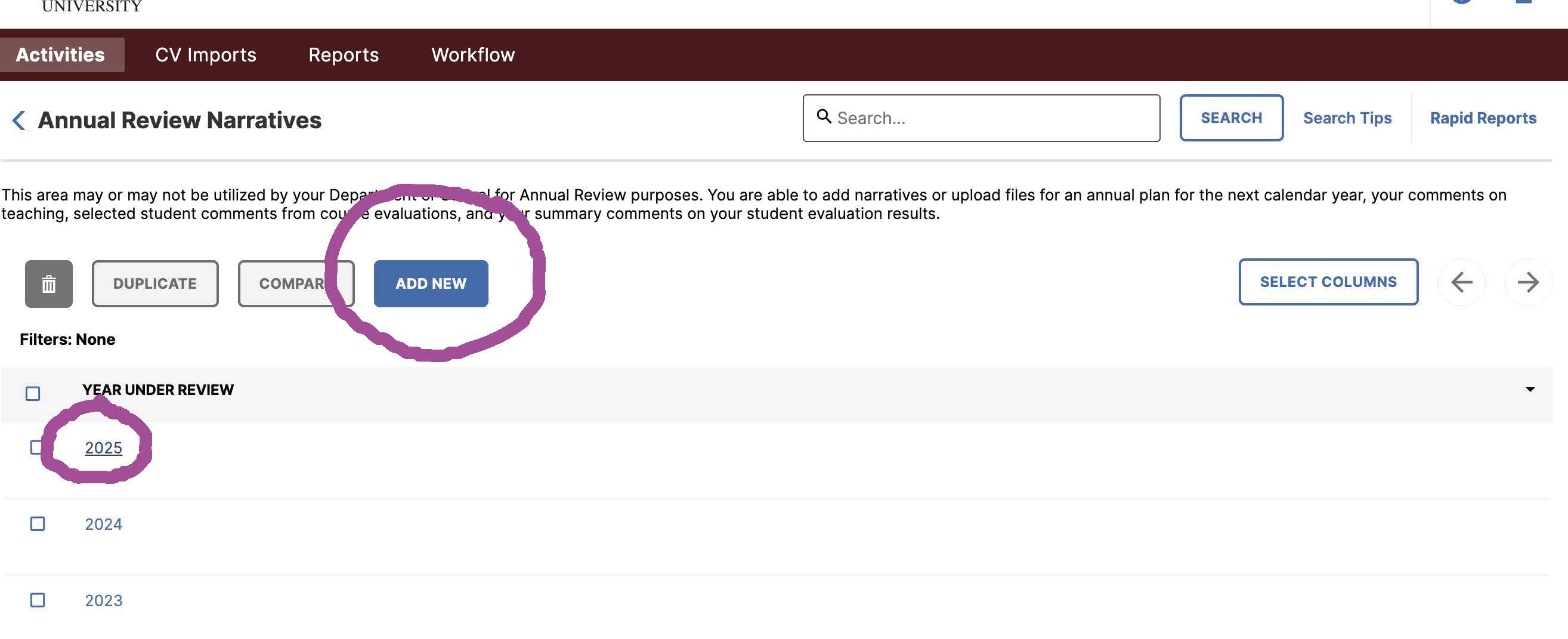

STEP #3: Click Add New.

STEP #4: Type in “2025.”

STEP #5: Type/paste in your Comments on Teaching for the Year Under Review. DO NOT attach files.

STEP #6: Skip “Annual Plan Narrative”

STEP#7: Skip “Upload Comments on Teaching”

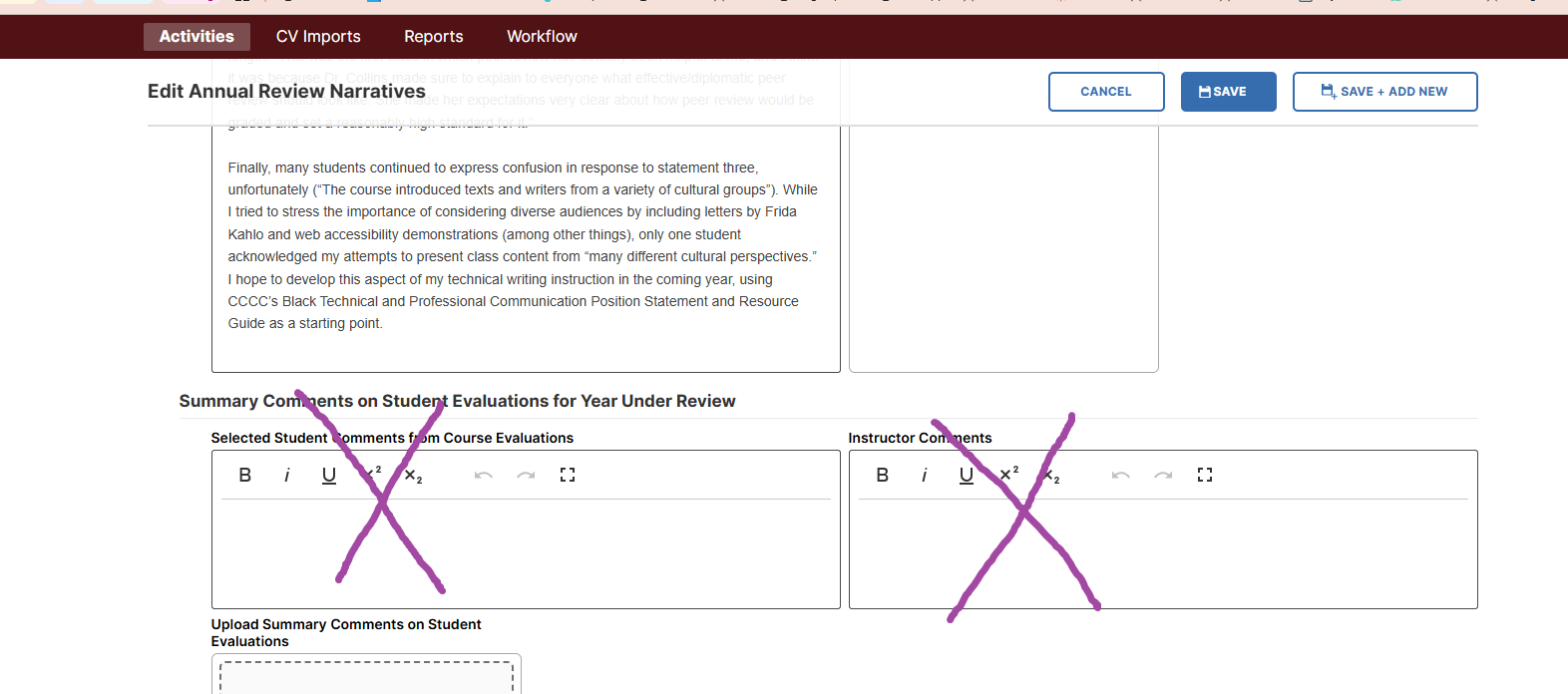

STEP #8: Skip “Summary Comments on Student Evaluations” and “Instructor Comments.”

STEP #9: Click Save.

SERVICE: Lecturers are not required to document service or scholarly/creative activity.

Digital Measures Submission

To create your 450- to 500-word teaching narrative (see samples at the bottom of this page):

- Log in to Digital Measures

- SCROLL PAST “Teaching” to the bottom of the page and under Annual Review, click Annual Review Narratives. (Do not use the “Teaching” section for your annual review).

- Click + Add New Item.

- For Year Under Review, type 2025.

- Skip Annual Plan for Coming Year.

- Type/paste in Comments on Teaching for Year Under Review. DO NOT attach files.

- Skip Selected Student Evaluations

- Skip Service Activities

- Click Save.

To submit your annual review . . .

- Click Workflow.

- From your Inbox, click English Lecturers Annual Review.

- Check to make sure your report is current. If not, hit Refresh Report.

- Click the PDF icon next to the report. The report will open, and you will be able to review it.

- If you need to make changes, click Manage Activities, make your corrections/additions, and begin the submission process anew. Be sure to click Refresh Report to reflect these changes.

- Return to the Workflow task.

- Click Save to save your progress and return later. Click Submit to submit your report. Submissions are final. Resubmissions require system administrator intervention.

-

Sample Annual Review Teaching Narratives

-

Shannon Shaw's Annual Review Teaching Narrative

Teaching

In 2024, I piloted three new assignments for 1321. The first was an environmental policy proposal for the city of San Marcos. The proposal included an executive summary, overview, discussion of alternatives, recommendation, and implementation. I received thoughtful, detailed, and thorough proposals, some of which I recommended students submit to the Writing Center essay contest. Additionally, students generally liked the assignment as one student wrote, “the policy proposal assignment was unique and very enjoyable.”The second pilot lesson, Graphing the Human Footprint, involved students graphing and interpreting climate data. Using historical data points, students graphed metrics associated with climate-change causes such as CO2 concentration, species extinctions, number of motor vehicles, GDP, energy consumption, and others. We discussed as a class what the data indicated, and they wrote about their findings. In another new major assignment, students conducted a sustainability literacy interview. After the first few weeks of learning sustainability basics, the class generated fifteen questions to ask their peers or family members. They then wrote an analysis and reflection about the state of general sustainability literacy. While both assignments engaged students, they could be more robust and more specifically related to course goals. One student summed the class up well, “This course should be required for all students because sustainability is necessary for the future of the entire world, and everyone in it. 100000/10 course.”

Two lessons for 1320/1321 that are old and not engaging for students anymore are ones for in-text citations and works cited page generation. Over the years, I’ve revised the lessons to include Writing Across Disciplines: different writing styles such as APA and Chicago, types of information they prioritize, and how they dictate writing style rules. I’ve also added information about qualitative and quantitative research. However, this spring I will have students practice APA style in their policy proposal and practice qualitative research methods in their literacy interviews.

Even though my citation and works cited lessons need updating, my focus on research practices made an impact on my students. One student wrote, “I have learned how to do research before writing an essay, and the importance of a rough draft.” Another wrote, “My approach to research has improved and become more organized because of this class.” Finally, when asked if the course improved their skills and increased their knowledge, one student replied, “fo sho.”

As I wrote in last year’s Annual Review, I had issues with some Tech Writing students failing to understand the concepts of systems thinking. As a project management tool for mitigating or eliminating problems in professional processes, Systems Thinking is important for Tech Writing students to understand and practice. The daily grades completed before the major assignments seemed to be where they struggled to understand. I left extensive comments on these low-stakes assignments; the comments I made were mostly clarifying and using their own examples as a guide for how to apply the concepts. Having them review my comments on the low-stakes assignments helped them successfully implement the concepts in the major assignment.

-

Mark Hernandez's Annual Review Teaching Narrative

Annual Review 2024 – Mark Hernandez

In all my First-Year English courses, peer review is one of my ongoing revision goals. One way that I emphasized the significance of peer review is by doing smaller workshops on minor assignments (such as introductions, reader response assignments, and in-class writing) in addition to the main ones for the major papers. The smaller workshops served as a practice run, and I reminded them that peer reviews help make them better readers and writers. I also gave guiding questions with the smaller peer reviews. Most of the students said they felt more confident presenting their work to others through these low-stakes assignments. Because they had already done smaller peer reviews, the major paper peer reviews seemed more engaging; the students did a better job discussing the drafts and left better comments. Throughout the semester, I constantly reminded them that revision is an important part of the writing process, so I also gave them the opportunity to revise after meeting with me.

I added some additional in-class, hand-written prewriting components to each major essay to combat the rise of AI. Each essay unit included an essay plan, several smaller in-class writing assignments, followed by a rough draft, and ending in the final draft and a reflection. This not only helped them with revising, but also with time management because the smaller assignments could be revised into the final essay. One student writes that “the slow build up with the essays … really helped me be prepared.” The smaller assignments and in-class writing kept the students on track with deadlines and many students commented that they didn’t feel as overwhelmed and didn’t procrastinate as much as they typically do.

In 2330, most of the students made excellent connections and thoroughly answered prompts designed to make connections to various texts throughout the semester. One student writes, “This course was challenging, and it did require creative thinking. The class required creative and active discussion in-class, which motivated students to participate and read the texts provided. Exams and essays required students to think creatively in their responses.” Additionally, while I do hold a peer review and discuss writing about literature, it would be beneficial to dedicate a bit more time to this since these courses are writing intensive. One student comments that they would’ve liked “[b]etter workshops and advice in order to improve our writing on the papers.” One goal next time I teach this course is to focus a bit more on the process on writing about literature. Typically, I do have a lesson and some in-class writing assignments focused on paragraph structure and writing about literature; however, I would like to expand this further by incorporating a more variety of writing assignments that are connected to the papers.

-

Jessica Martinez's Annual Review Teaching Narrative

My 1320 students write a five-to-seven-page argumentative essay with at least five credible sources and one counterargument. I broke the essay into four sections—planning, researching, outlining, and peer reviewing—so that students could more easily develop topics and claims. One student commented, “This course improved my ability to write, and improved my ability to properly prepare before writing an essay.”

This semester, I added more classes that focused on why the annotated bibliography was necessary and how to structure it. One 1320 student commented, “A major challenge I had within the course was creating an annotated bibliography. I never made one before, so I had to overcome the difficulties with learning something new.” While most students found learning MLA tedious, I believe framing the annotated bibliography as a means of “showing one’s work” helped them realize that researching and proper documentation is a crucial part of the writing process.

Last semester, a student in my 1320 wrote, “a lot of the classes were repetitive and covered the same content over and over again.” I believe this was the result of group presentations I assigned over the five types of arguments in our textbook, Everything’s an Argument. I noticed attendance and class participation declining as soon as students completed their presentation. However, this semester, I assigned chapter reviews of the five types of arguments. Students took the review home and completed it while reading the assigned chapter. This improved class participation while also helping students understand how to structure their classical argument essay. One of my main goals this semester was to improve attendance in my 1320 classes, so I implemented a bonus points policy in which students earned points towards their overall grade at the end of the semester. This motivated students to attend more than in the past.

While teaching 3315 in Fall 2023, I realized that I wanted to give students more time to draft for their workshops. This semester, I had the opportunity to teach 3348. I decided to use George Saunder’s A Swim in a Pond in the Rain and Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad for the first half of the class. Saunder’s book introduced students to structure, form, and theory, while Egan’s reinforced the elements of craft. This led to great class discussions while giving students time to write for their workshops. Students were assigned a craft analysis essay in which they had to write about two modern short stories. I previously assigned this in 3315, though, most students approached this essay as a literature paper and did not write about contemporary stories. For 3348, I gave them a list of over twenty recently published stories to write about. I received positive feedback about the stories, and students said they were excited to incorporate similar elements of craft in their fiction.

-